You don’t have to agree with everything professor Dawkins stands for to acknowledge that, since Carl Sagan, he has been one of the most prominent science popularizers lately. He has succeeded in putting his message across several times throughout his more-than-30-year-long career as a science writer. I decided to draw up a list of his books and give a short account of each, though I must admit I haven’t read them all myself.

The Selfish Gene (1976)

The Selfish Gene (1976)

The one that made him famous and controversial overnight. In it he argues that natural selection acts on genes, not on the level of populations as previously held. This is where he invented the term meme as a unit of cultural transmission, analogous to the gene. This is still the book most people identify Dawkins with, although some of the ideas might seem outdated.

The Extended Phenotype (1982)

The Extended Phenotype (1982)

Here he elaborates on the ideas put forward in The Selfish Gene, but in a way that’s a tiny bit more technical, while retaining its readability. Dawkins regards this book as his most significant contribution to evolutionary biology. Subtitled The long reach of the gene, phenotypes are not necessarily limited to the organism itself, but can be manifestations extended beyond that. Think of the beaver’s dam.

The Blind Watchmaker (1986)

The Blind Watchmaker (1986)

One of his most popular works, in it he takes on the task of explaining how evolution works, using the metaphor of a blind watchmaker, meaning that evolution has no purpose in creating endless forms. He wrote the book to, in his own words, “persuade the reader, not just that the Darwinian world-view happens to be true, but that it is the only known theory that could, in principle, solve the mystery of our existence.”

River Out of Eden (1995)

River Out of Eden (1995)

His shortest book, it basically contains summaries of topics mentioned in his previous books. He goes on to explain evolution through genes and human ancestry. He also contemplates how Darwinian evolution may take place outside our planet. The title comes from Genesis. Illustrations by his wife, actress Lalla Ward, can also be found in here.

Climbing Mount Improbable (1996)

Climbing Mount Improbable (1996)

This work is a book-long rebuttal of the obnoxious creationist claim that the chances for complex organs, like the bacterial flagellum or the human eye, to evolve are so meagre that they surely must be the handiwork of an intelligent designer. At first glance it looks improbable, but evolution moves across the adaptive landscape gradually, and given enough time, it will certainly reach the peak of that metaphorical mountain.

Unweaving The Rainbow (1998)

Unweaving The Rainbow (1998)

The relationship of science and art is dissected here. John Keats once blamed Isaac Newton for destroying the rainbow by simply explaining it. He tries to persuade the reader that natural wonders like the rainbow do not necessarily lose aesthetic value once their mystery is solved. To the contrary, dissecting nature has the capacity of actually enhancing its beauty.

A Devil’s Chaplain (2003)

A Devil’s Chaplain (2003)

This is a collection of essays written over the years. The subtitle says it all: Reflections on hope, lies, science, and love. The topics are diverse, it contains a eulogy for his friend Douglas Adams, an essay that disrobes postmodernism, as well as an open letter to his then minor daughter, giving her advice on how to evaluate evidence and view things with a critical and open mind.

The Ancestor’s Tale (2004)

The Ancestor’s Tale (2004)

In the fashion of The Canterbury Tales, Dawkins takes a pilgrimage to the dawn of evolution starting from humans. Along the way he stops at every major cornerstone to relate the most interesting facts (tales), and what we need to know about that particular ancestor. Spanning billions of years he finally arrives at the origins of life. My personal favourite. It’s time for a re-read, I reckon.

The God Delusion (2006)

The God Delusion (2006)

Sold over 2 million copies, this one virtually made him an international superstar and an iconic figure of atheism. It became one of the four great books of the so-called “new atheism”, the others being The End Of Faith by Sam Harris, God Is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens, and Breaking The Spell by Daniel Dennett. Not the easiest read, but well worth the effort.

The Greatest Show On Earth (2009)

The Greatest Show On Earth (2009)

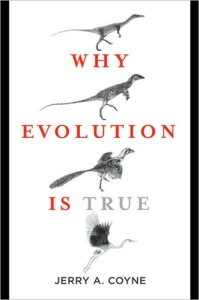

He had written books on evolution for decades, before he realized he never actually laid out the evidence for it. With the upsurge of the intelligent design movement and its dumbed down version creationism, he felt the need, alongside other notables like Jerry Coyne or Neil Shubin, to lamentably write this book. The evidence is clearly demonstrated here, to deny it, like all creationists do, would be an act of lunacy.

As revealed in recent interviews, Dawkins is currently working on a children’s book, in which he intends to explain evolution in a way that’s understandable even to the youngest of the inquirers.

Jerry A. Coyne from the University of Chicago is a distinguished biologist of

Jerry A. Coyne from the University of Chicago is a distinguished biologist of