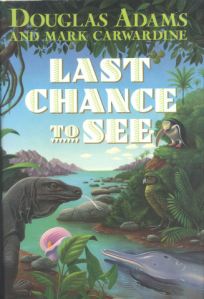

In 1990, a book appeared in the shops called Last Chance To See. It was the account of the journeys made by Douglas Adams and zoologist Mark Carwardine in their pursue of some of the most endangered animals on the planet. Twenty years later, the same zoologist hooked up with Stephen Fry, a great friend of the late Douglas Adams, and together they revisited the same animals. This time not only a book was released, but a spectacular six-part BBC documentary series came along with it as well.

In 1990, a book appeared in the shops called Last Chance To See. It was the account of the journeys made by Douglas Adams and zoologist Mark Carwardine in their pursue of some of the most endangered animals on the planet. Twenty years later, the same zoologist hooked up with Stephen Fry, a great friend of the late Douglas Adams, and together they revisited the same animals. This time not only a book was released, but a spectacular six-part BBC documentary series came along with it as well.

Dr. Carwardine is an extremely knowledgeable naturalist and conservationist, author of about 50 books. Stephen Fry, one of my favourite public figures, is an out of place man, he simply doesn’t know what he’s doing in the jungle. He’s a gadget freak, first thing he does in the middle of the Amazonian Basin is to check if there’s broadband available on one of his several iPhones. Awkward and unfit, he falls on his arm and breaks it in three in the very first episode. The comic value added by Stephen is a major factor in propelling the film and in setting the series apart from other nature programs.

At the outset, this unlikely duo tries to track down the Amazonian manatee, a peaceful aquatic mammal that looks like an oversized underwater bulldog, but can’t find any. What they find is the pink river dolphin or boto, which still thrives in reasonable numbers, as opposed to the Chinese river dolphin that has gone extinct since Douglas and Mark encountered it in the Yangtze. In the next episode they hop over to Africa to search out the Northern white rhino. Along the way, they meet chimps, wild elephants and gorillas, but eventually decide against entering the rhino’s territory stricken by civil war. In Madagascar, a pygmy chameleon, a mouse lemur and the indri are the main sensations, before finding the aye aye, one of the rarest primates, up in a coconut palm.

In Indonesia, they find themselves surrounded by Komodo dragons and releasing newly hatched sea turtles on the beach. In New Zealand, we learn that the black robin came back from the brink of extinction from as few as 5 individuals and only one breeding female. This success story inspired those responsible now for the rescue of the kakapo, which a couple of years ago dwindled to a mere 40 individuals. All were captured and translocated to a tiny island south of New Zealand, and due to an effective breeding program their numbers now climbed up to 123. One of the most memorable moments of the series was when a male kakapo tried to mate with Mark’s head, much to Stephen’s amusement:

The kakapo’s clumsiness was most endearingly described by Douglas Adams:

It is an exceptionally fat bird (a good-sized adult weighs roughly two or three kilograms) and its wings are just about good enough to waggle about a bit if it thinks it’s going to trip over. But flying is completely out of the question. Strangely, not only has it forgotten how to fly, it also seems to have forgotten that it has forgotten how to fly. Legend has it that a seriously worried kakapo will sometimes run up a tree and jump out of it, whereupon it flies like a brick and lands in a graceless heap on the ground.

The final episode is spent tracing the blue whale off Baja California in the Sea of Cortez, and while they’re at it, they collect and analyze sea lion poo, and measure a whale shark. The crew also observes the Humboldt squid, a fierce apex predator that’s gradually taking the place of sharks at the top of the food chain.

I haven’t read the book yet, but the series I thoroughly enjoyed. This is no ordinary entertainment, carried out by BBC’s decades-old professionalism conveying amazing wildlife shots and a profound message.